GCPEA News

How Canada Can Protect Schools in War Zones

The World Post, September 28, 2016

“Sebastian” wore the most dazzling white school-uniform shirt, matched with the dirtiest of sneakers. We met inside a church in the town of Mweso in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, because he wanted to tell me about what happened at his school.

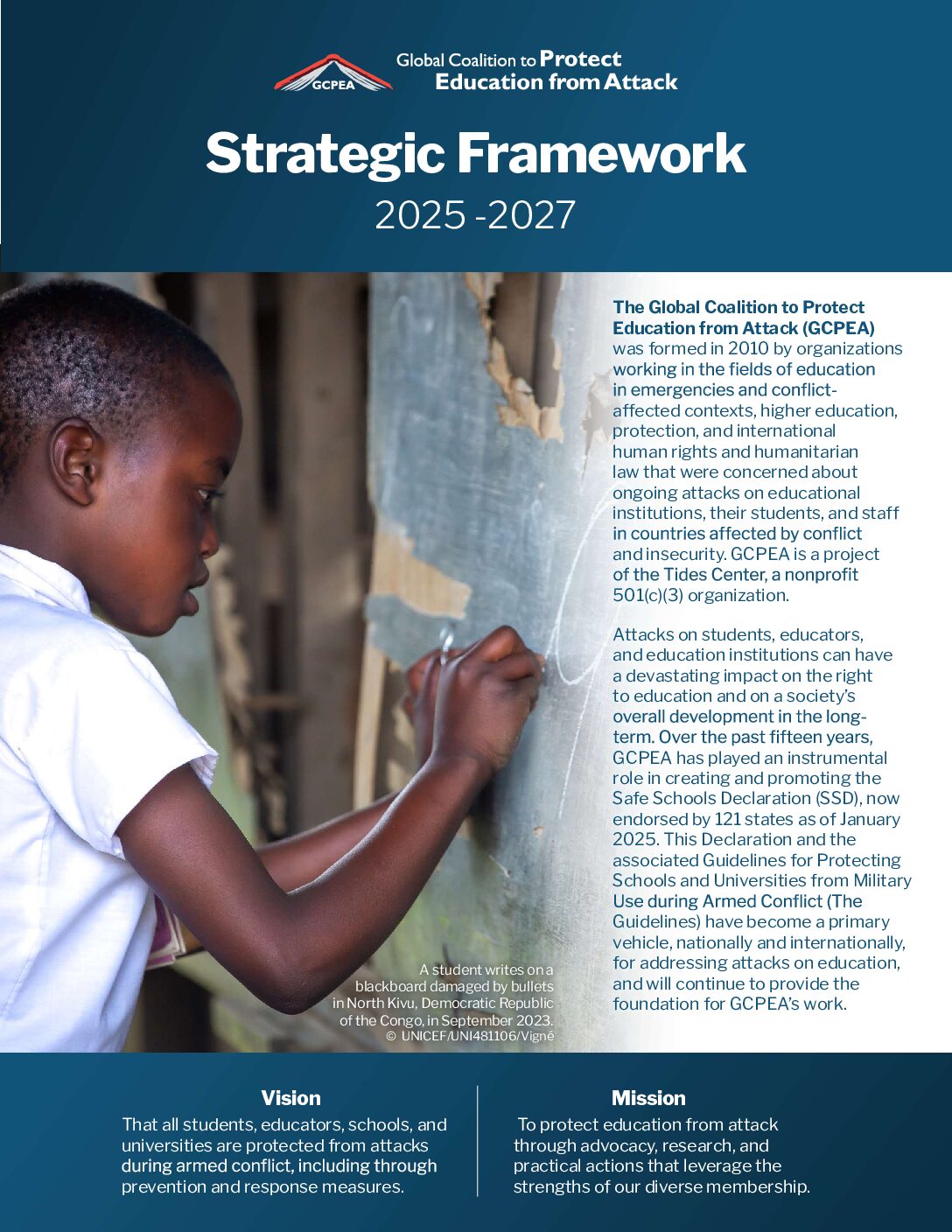

Staring intently at his mud-caked shoes, the 12-year-old told me how earlier in the year soldiers from the Congolese army had taken over a few classrooms in his school to use as a barracks and temporary base. Sebastian explained how he’d valiantly tried to continue his studies in a classroom next door, literally in the line of fire should the rebels attack. When we spoke, he said he hoped that “just maybe” he’d soon be able to continue his studies in peace.

Well, things are looking up for students like Sebastian in Congo. Last month the Congolese government joined an international commitment known as the Safe Schools Declaration. Announcing the endorsement at the United Nations Security Council, Congo’s ambassador declared that doing so demonstrated his country’s commitment to never again use schools for military purposes. He cited a Congolese military order prohibiting the practice. This is good progress.

Yet it will surprise many to learn that unlike Congo, Canada does not have military policies or rules explicitly saying its armed forces will refrain from using schools for military purposes. Nor has Canada joined the 56 countries that have already endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration. It should do both.

Countries that have signed the Safe Schools Declaration not only agree to restore access to education faster when schools are attacked, but they also agree to make it less likely that students, teachers, and schools will be attacked in the first place. They seek to deter such attacks by making a commitment to investigate and prosecute war crimes involving schools. And they agree to minimize the use of schools for military purposes, such as for barracks or bases, so as to not convert schools into targets for attack.

Perhaps most importantly, the declaration builds an international community committed to respecting the civilian nature of schools, and developing and sharing examples of the best practices for protecting schools from attack and military use.

The Harper administration refused to join the declaration when it was opened in May 2015. Officials contended that the existing laws of war – the basic minimum standards by which states and non-state actors must fight – were sufficient. They saw no need for Canada to try to do any better.

Yet Canada has traditionally been at the forefront of advocating that even during times of war, the country must maintain respect for humanity. Whenever Canada has the capacity to take sensible steps to limit the harm and destruction caused by war, it should.

Such humanitarian principles led Canada in 1996 to challenge the world to ban the production and use of anti-personnel landmines. The resulting Ottawa Treaty has now been ratified by 162 countries, saving countless civilian lives around the world.

These principles led Canada in 2002 to be the first nation to ratify a treaty aimed at ending the use of child soldiers around the world. And, during its last stint on the UN Security Council, to make sure that the world’s highest forum for international peace and security finally dedicated time to discuss how armed conflict affects children.

The Safe Schools Declaration is not a hypothetical exercise. As a NATO member with troops deployed overseas, and more expected to soon be sent as peacekeepers, Canada should ensure that its presence abroad will never impede children’s ability to go to school in safety. The 600 Canadian troops newly assigned for peacekeeping missions will be obliged to follow the UN’s requirement that they never use schools in their operations—an even more stringent standard than in the declaration. So signing up should present few challenges for these forces.

Across Canada approximately 10,000 recently arrived Syrian refugees are experiencing something new: a safe school. We’ve interviewed hundreds of Syrian children and their parents, and many told us that one major reason for fleeing their homeland was because they couldn’t get an education – because their schools were targeted, used by the military, or simply not functioning. And it’s not just Syria – refugee children from other countries where schools are placed in the crosshairs, such as Afghanistan, Congo, Nigeria, and Somalia, all now attend safe schools in Canada.

That’s great news – but there is even more Canada could do to help children still living in countries where schools have become battlegrounds. If you agree that Canada should endorse the Safe Schools Declaration, then please join our call on Human Rights Watch’s website.

Bede Sheppard (@BedeOnKidRights) is deputy children’s rights director at Human Rights Watch.