GCPEA News

Peshawar attack ends a bad year for school children across the World

Sunday Morning Herald, December 19, 2014

Matt Wade, Senior writer

The horrifying slaughter of students in the Pakistani city of Peshawar caps a terrible year of violence against school kids.

The sickening scale of the Taliban’s assault on the Army Public School has sparked global fury. But it’s just one of hundreds of attacks on schools across the world in 2014.

Some of them have captured global headlines – like the abduction of 300 girls from a secondary school in Nigeria by Boko Haram gunmen in April. Boko Haram militants are under suspicion for targeting children again this week after more than 180 women and children were abducted from a remote village in north-eastern Nigeria on Sunday. About 35 people were killed in the raid and the captives were reportedly taken away in “two open-top trucks.”

But many attacks on the education of children get little attention. Save the Children’s recent “No Child Left Behind” report documented 78 attacks on schools, teachers and students in Pakistan and at least 73 attacks on schools in Afghanistan in 2013. During this year’s conflict in Gaza 148 schools were damaged or destroyed the report said.

Unicef branded the Peshawar attack and the reported deaths of 15 school girls in a car bomb attack in Yemen – also on Tuesday – “a dark day” in a bleak year for children around the world.

“Repeatedly this year, schools have been targets of violence, with students, teachers, and school staff paying a terrible price,” it said. “Throughout 2014, children have been affected as never before in recent memory by violence and extreme hatred.”

Paul Ronalds, the chief of aid agency Save the Children, pointed out that the tragedy in Pakistan was part of a much wider and alarming global trend “in which more students, teachers and places of education are being targeted or used by armed groups.”

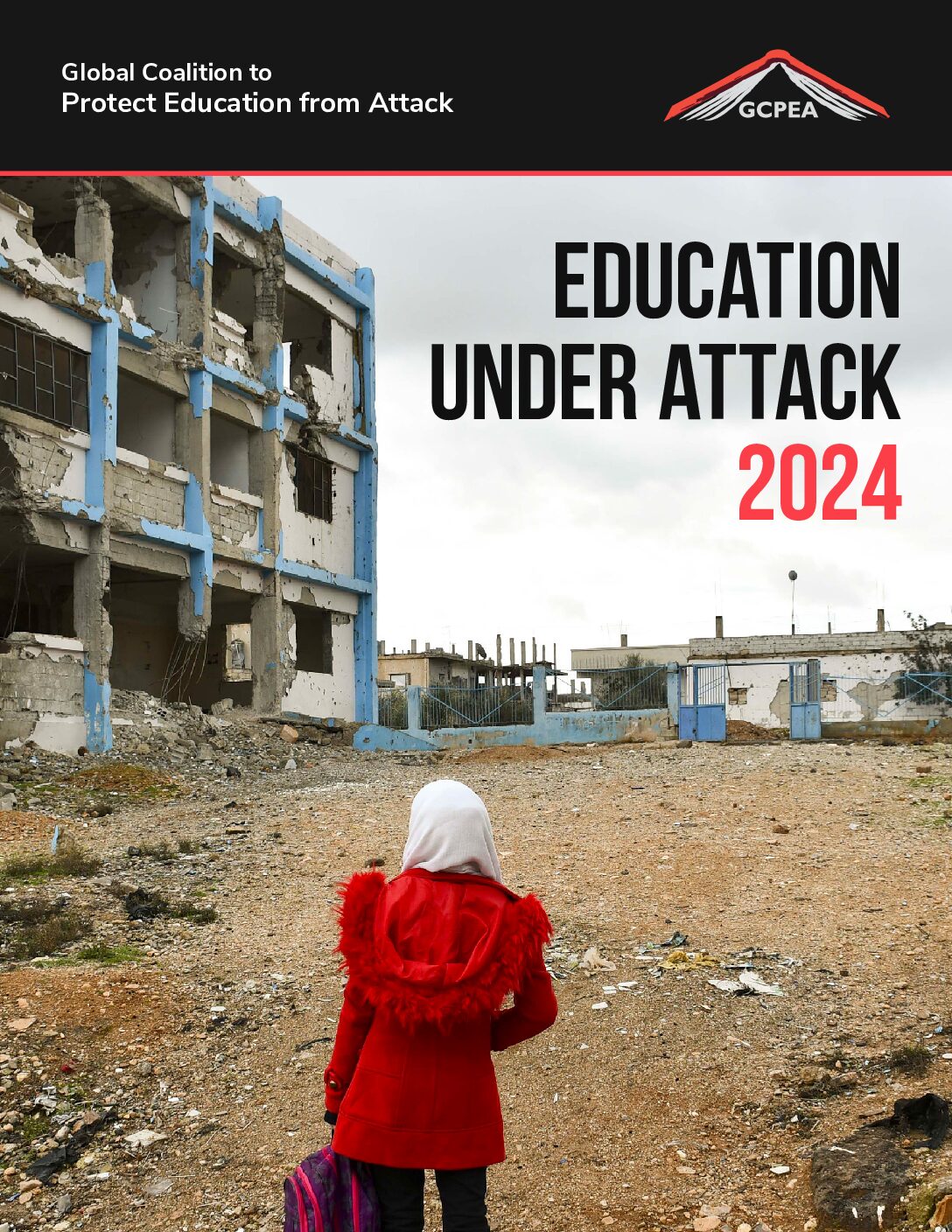

The Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack has identified 70 countries where educational institutions were targeted during the past four years, including 30 where there was a pattern of deliberate attacks. In Syria alone, at least 3,465 schools were destroyed or damaged during the recent conflict. The Coalition has documented the recent killings of hundreds of students and educators, with many more injured. It’s likely hundreds of thousands study, or teach, in fear.

Schools and other educational institutions are often used by fighting forces during conflict because of their central locations, solid structures, ready toilets, kitchens, and other facilities. Schools and universities have been used for military purposes such as bases, firing positions, armouries, and detention centres during conflicts in at least 25 countries over the past decade.

The recent spate of major humanitarian crises has also taken a terrible toll on children’s education. Nearly 9 million students have been forced out of school in the past year by the world’s six biggest emergencies, the “No Child Left Behind” report says. The Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone and Liberia alone has pushed 3.5 million children out of school while the crisis in Syria has prevented 2.8 million from attending classes. Another 2.4 million children have missed out on school because of emergencies in South Sudan, the Philippines, the Gaza Strip and Iraq.

There is a push for all states – including Australia – to adopt the “Lucens Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict.” The guidelines urge all parties in armed conflict not to use schools and universities for any purpose in support of the military effort and to preserve education as a safe zone in armed conflicts. While the guidelines – launched in Geneva this week – won’t prevent every attack on education, Paul Ronalds believes they could “help limit the use of schools as military bases or prevent them from being targeted so that school children are not killed or injured.”

Tuesday’s attack in Peshawar has been described as the worst in Pakistan’s long and bloody history of militant violence. Kailash Satyarthi, the Indian child rights campaigner who shared this year’s Nobel peace prize with Malala Yousafzai, said the massacre marked “one of the darkest days of humanity.”

That darkness should draw attention to the fact that attacks on schoolchildren are all too common.

Matt Wade is a Fairfax journalist and a former South Asia correspondent.