GCPEA News

Rebuilding for the Future: A Spatial Analysis of Education Reconstruction in Yemen

Alexander Kochenburger, New Lines Institute, July 12, 2023

As Yemen’s conflict enters its ninth year, a protracted cease-fire within the country and a recent normalization in relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran (the conflict’s main external sponsors) have led to increased optimism for a formal end to the fighting. The conflict in Yemen has led to the deaths of more than 377,000 Yemenis. It has left 25 million people in need of humanitarian assistance and more than 5 million at risk of starvation. Control of the country remains divided between the al-Houthi movement, the Southern Transitional Council, and the internationally recognized government. Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula continues to maintain a strong presence in several areas.

While current negotiations between the Saudis and al-Houthi forces may lead to a cessation of hostilities, international observers have warned that more inclusive and extensive efforts will be needed to reach a sustainable resolution to the conflict. However, reconstruction efforts must start immediately.

One area that will require significant attention and investment is education. The country’s conflict has severely damaged an already vulnerable education system: Schools have been destroyed by ground fighting and air strikes, taken over by armed groups and used as training facilities, and reused to host internally displaced persons. Many public school teachers have not received salaries in years, leading to an exodus from the profession and extremely high student-teacher ratios. Unenrollment rates for children, and especially young women and girls, have skyrocketed amid the violence. Parties to the conflict have recruited thousands of these children to join their forces.

International policymakers have increasingly recognized the urgent need for education reconstruction. USAID is implementing an $18 million grant for school rehabilitation, while other non-governmental organizations have announced campaigns of their own. Immediate and comprehensive education reconstruction is needed to secure the right to education for young Yemenis, expedite the reintegration of the millions of children out of school into society, and prevent a lost generation. As policymakers design and implement reconstruction programs, both now and after an eventual cessation of hostilities agreement, efforts that do not consider the country’s damaged education system will undermine long-term goals of finding a durable resolution to the conflict and stabilizing the country.

With this understanding, policymakers should focus on four questions to help guide education reconstruction efforts. Each of these questions can be guided by spatial analysis techniques to highlight areas of need in the country. While education reconstruction efforts should be implemented across Yemen, the realities of nearly a decade of war have left some governorates with particularly dire needs. Policymakers should also consider which party controls each of these areas, as Yemen’s conflict has produced a fractured country with control of territory divided between many different parties.

- Where has education infrastructure sustained the most damage from the conflict?

- Where have the largest number of children been recruited to join the armed forces of various parties?

- Where are student-teacher ratios the highest?

- Where are unenrollment rates of young women and girls the highest?

Analyzing these education needs across Yemen’s governorates can lead to several recommendations for education reconstruction efforts that will support the country’s transition and reconciliation, as well as subsequent regional stability. USAID and other international organizations can assist governing institutions across the country, as well as the country’s civil society, by providing funding and encouraging policies that will rebuild and transform the country’s education system and end the militarization of schools.

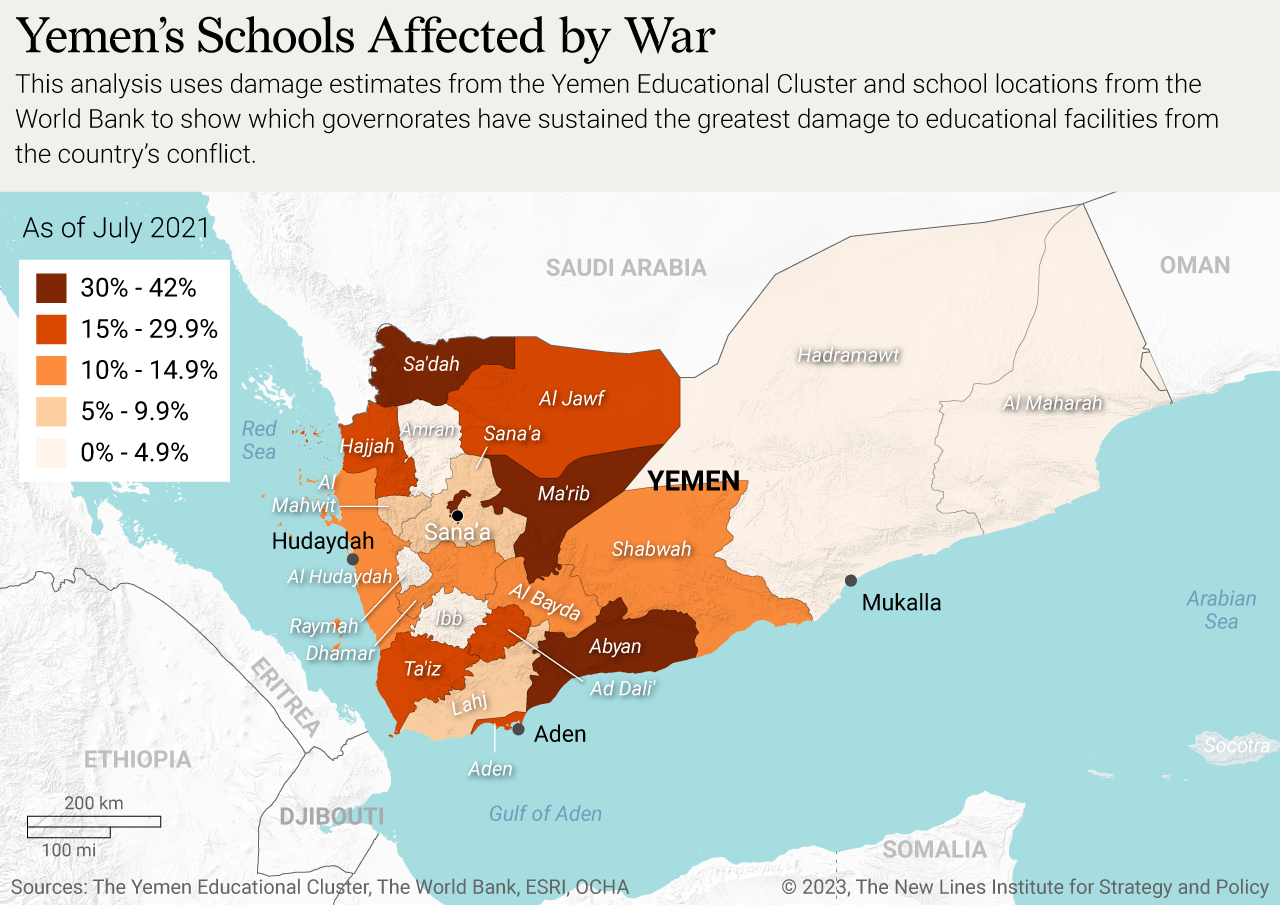

Schools Damaged by the Conflict

As of July 2021, the Yemen Education Cluster estimated that the country’s conflict has directly affected more than 2,300 schools in Yemen. Most of these schools are entirely out of use, which contributes to the large number of children out of school and the overcrowding of many nearby education facilities.

As seen on the map, the following governorates have the highest percentage of their educational facilities affected by the conflict, and thus should be targeted for immediate reconstruction and rehabilitation efforts: Sana’a City (controlled by al-Houthi forces), 42%; Abyan (largely controlled by the internationally recognized government), 35.8%; Sa’dah (controlled by al-Houthi forces), 33.6%; and Ma’rib (under partial control by al-Houthi forces and partial control of the internationally recognized government), 33.4%.

Ma’rib governorate has seen some of the war’s heaviest fighting. Abyan governorate has also seen frequent clashes between government-backed forces, the Southern Transitional Council, and al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

Other Education Reconstruction Considerations

Aside from rebuilding physical education infrastructure, there are several other ways that a spatial analysis can guide education reconstruction efforts by highlighting areas of need, according to different metrics, in the country.

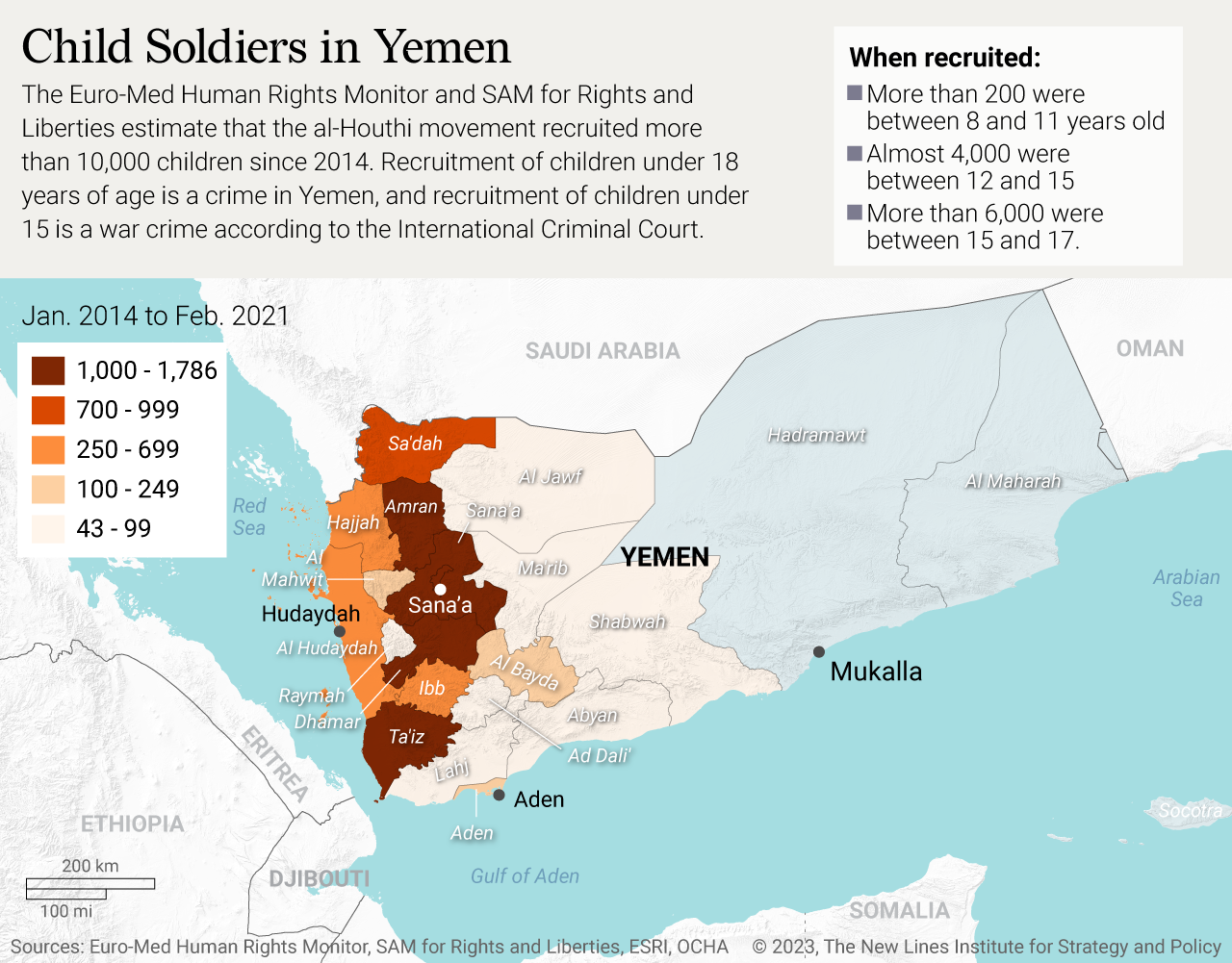

The Recruitment of Child Soldiers

One consideration involves locating governorates with the highest numbers of child soldiers. While all parties are guilty of recruiting child soldiers, including the internationally recognized government, this analysis focuses on the al-Houthi forces’ recruitment of children. The armed movement is widely believed to be the largest perpetrator of the crime and most of the available data concerns their targeting of children. The al-Houthi forces have been recruiting young boys to fight and young women and girls to act as informants, guards, and paramedics.

Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor and SAM for Rights and Liberties estimate that members of the al-Houthi movement have recruited more than 65% of these children through financial temptation. Most of these children come from extremely poor families, and the al-Houthi group has often offered salaries of up to $150/month. In many cases, the al-Houthi forces have recruited these children directly out of schools, demonstrating the importance of enacting polices that end the militarization of schools.

The al-Houthi forces have recruited the largest number of child soldiers in the following governorates it controls: Amran (1,786 children), Sana’a (1,478 children), and Dhamar (1,450 children)

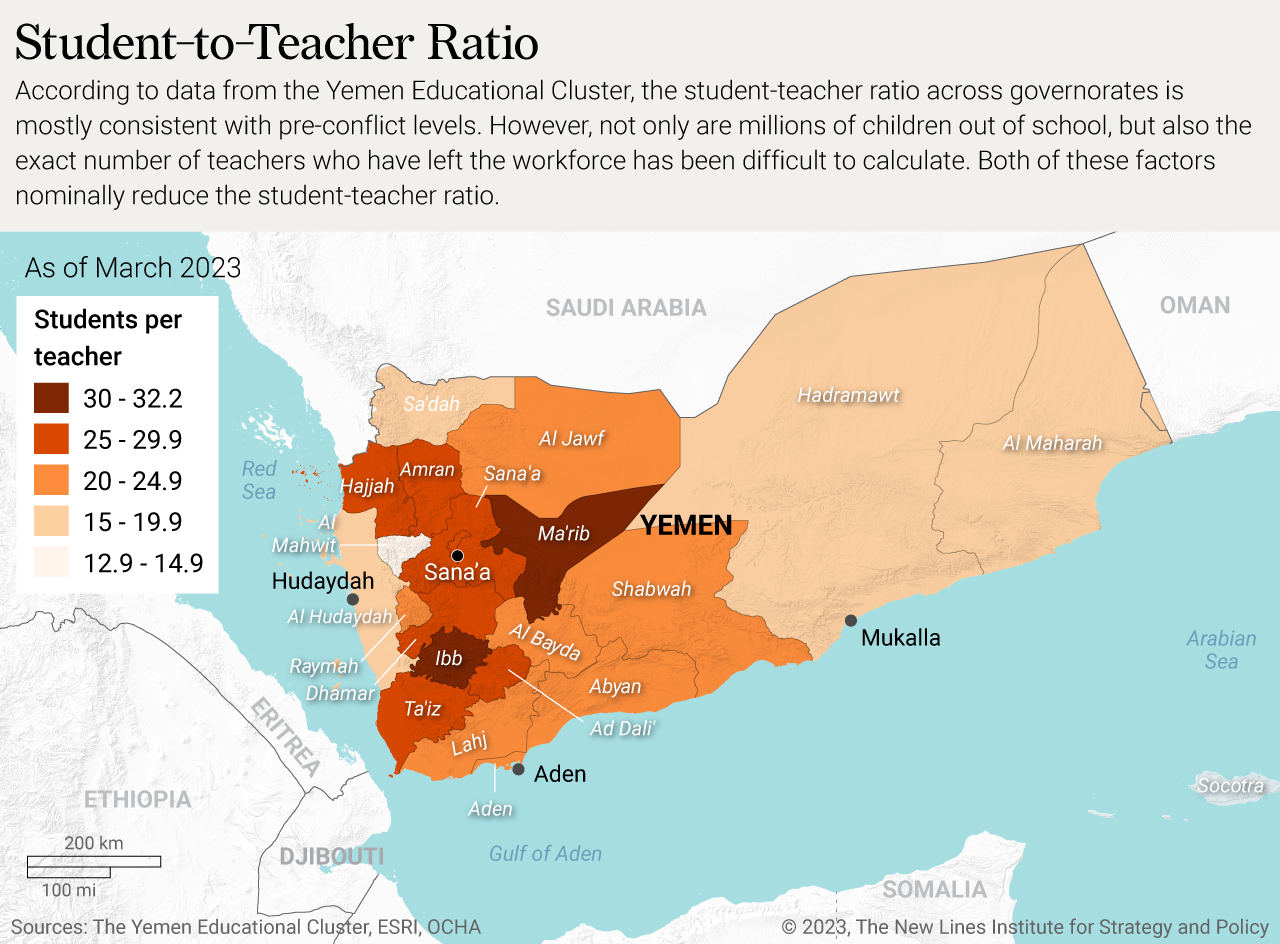

Student-Teacher Ratios

A second consideration is student-to-teacher ratios and finding the governates where those ratios are highest. Teachers’ unions across the globe have stressed that this is one of the most important education metrics, as lower ratios generally lead to greater student learning and achievement, stronger mentorship and support systems, and reduced teacher burnout. Teacher-student ratios vary widely from country to country. In 2016, the ratio was a little over 10:1 in Norway, and approximately 16:1 in the United States. Before the start of the conflict, the ratio in Yemen was around 30:1.

The country’s conflict has ignited a exodus of teachers from the profession. Not only have educators been threatened and harassed by parties to the conflict to openly align with them, but also Save the Children estimates that more than 50% of Yemen’s teachers have not received regular pay since 2016.

Once a cessation of hostilities is reached, it will be possible to calculate student-teacher ratios in each governorate with more precision. Even if the current ratios stand, they are far too high to ensure a quality education for Yemeni students. In 2014, a UNICEF report stressed the importance of preventing overcrowded classrooms in order to boost enrollment and retention rates. These needs have only been compounded by almost a decade of violent conflict.

It will take many years of reconstruction efforts for Yemen to reach this goal. In the meantime, current data shows that these governorates have the highest enrolled-student-teacher ratios: Ma’rib governorate (under partial control by al-Houthi forces and partial control of the internationally recognized government), 32.2:1; Ibb governorate (controlled almost entirely by al-Houthi forces), 31.5-1; and Ad Dali’ governorate (divided among the al-Houthi movement, the Southern Transitional Council, and the internationally recognized government), 29:1.

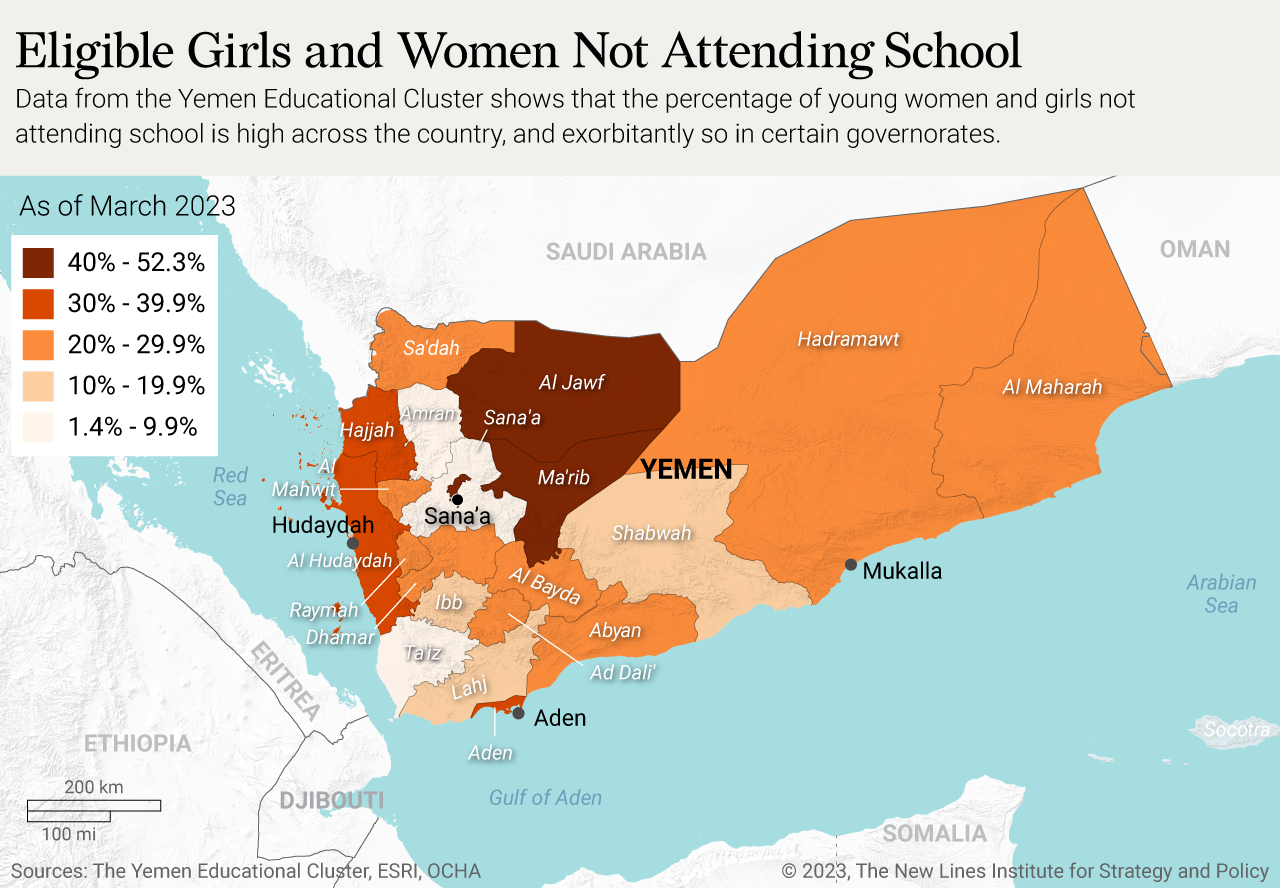

Unenrollment Rates of Young Women and Girls

A third consideration involves locating governorates with the highest percentage of young women and girls out of school. Before the start of the conflict in 2014, Yemen was making consistent progress on increasing girls’ access to education. In the years since, unenrollment rates for young women and girls have taken a turn for the worse. Conflict is not experienced equally across populations, and it particularly leads to greater insecurity for women amid the breakdown of public order and institutions and the spread of violence.

The International Rescue Committee issued a report highlighting several causes for the concerning rates of young women and girls out of school in Yemen. The report notes that many families have kept their daughters from attending schools due to safety concerns amid fighting in their neighborhoods. It also states that young women have been married at young ages due to financial concerns in their families; approximately 20% of households in Yemen are now headed by women under the age of 18.

When women are able to access education, they can achieve a higher standard of living, reduce the incidence of early marriage, exercise greater independence and agency, and contribute to their society’s growth. Along with rebuilding schools, lowering student-teacher ratios, and ending the recruitment of children into armed forces, this is a critical metric for Yemen to improve. Of all the governorates in Yemen, these have the highest unenrollment rates for young women and girls: Al Jawf (controlled by al-Houthi forces), 52%; Sana’a City (under al-Houthi forces’ control), 46%; and Ma’rib (split between the al-Houthi movement and the internationally recognized government).

Recommendations

Reconstruct Education Infrastructure Across Yemen, and Especially in Heavily Damaged Areas, with Sensitivity to Gender Considerations

Yemen’s education infrastructure will require significant support from the international community to recover from nine years of war. In governorates such as Sana’a City, Abyan, Sa’dah, and Ma’rib, more than one-third of schools have been affected by the fighting, and many of these are entirely out of use. In Sana’a City and Ma’rib, nearly half of eligible girls and young women are also unenrolled in school. As these governorates are not controlled by any single party, it is vital that policymakers work with a variety of local actors to implement reconstruction efforts.

Policymakers should ensure that education infrastructure is not just rebuilt but strengthened. There are many reasons for the high number of young women and girls out of school, but the government and international community can address a number of these by rebuilding in a gender-responsive way. Simply reconstructing destroyed schools is a start, as it will reduce the threats that women and girls face while traveling longer distances to attend the nearest school. However, research in Yemen conducted by USAID and other international partners has also shown that enrollment rates of young women and girls increase when schools have more teachers that are women and facilities (such as recreation areas and bathrooms) that are gender segregated. In its recent work in Yemen, USAID has recognized the importance of these considerations in driving up enrollment rates of young women and girls. Programs like these that are gender-responsive will help create safe and inclusive learning spaces that will increase enrollment and retention rates. Future work will also be needed to account for the unique needs of female educators in these contexts.

While Sana’a City and Ma’rib should receive priority funding, given the level of damage these governorates have sustained to their education infrastructure during the conflict, policymakers should implement these reconstruction and rehabilitation programs across the country. Doing so will inevitably introduce a level of complexity in navigating the divided and highly localized control of territory in Yemen, a reality that will likely remain to a degree even after an eventual cessation of hostilities agreement. In areas where the al-Houthi forces maintain a strong presence, close monitoring will be needed to ensure that allocated funds are actually used for education infrastructure, and not diverted for other uses as has happened with other forms of aid in the past. However, these efforts are critical to secure the rights of Yemenis and stabilize the country by lowering rates of children, and especially young women and girls, out of school and without empowerment to contribute to their country’s growth.

Enact and Encourage Policies that Put an End to the Militarization of Yemen’s Schools

The international community can help end the militarization of Yemen’s schools in a few different ways. To start, policymakers should consider instituting sanctions against high-level officials who commit the crime of recruiting child soldiers. In 2022, the al-Houthi group signed an agreement with the U.N. that promised to end their practices of recruiting child soldiers. The internationally recognized government has signed similar agreements in the past, but enforcement and implementation has remained an issue for all parties concerned. Given the level of international support that Yemen will need to finance reconstruction efforts after a cessation of hostilities, the international community likely has quite a bit of leverage in this area. The World Bank recently estimated that the total cost of reconstruction efforts in Yemen could be nearly $30 billion. In 2022, Yemen’s GDP was around $20 billion.

Policymakers can also encourage the next national government of Yemen, which will take shape after an eventual resolution to the conflict, to integrate the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict in domestic legislation. These non-binding protocols were created by international organizations, with the support of several governments, and define best practices for protecting education in areas of armed conflict and violence. Implementation of these guidelines would effectively put an end to practices in Yemen, largely but not exclusively committed by the al-Houthi forces, of recruiting child soldiers from schools and locating military personal within education infrastructure in general. These policies would not only help end the recruitment of child soldiers, but also ensure the safety of teachers and educators and produce more conducive learning environments. The international community should closely follow the demilitarization of schools in Amran, Sana’a, and Dhamar governorates, given the high number of child soldiers recruited from these regions.

Looking Forward

Ultimately, Yemen’s peacebuilding efforts must be attentive to the role education can play in driving and resolving conflict. Neglecting – or deprioritizing – education reconstruction will only leave children, and especially young women and girls, either out of school or attending heavily damaged and overcrowded schools; more vulnerable to the recruitment of armed groups; and without the education necessary to contribute to the future of their country.

USAID and other international policymakers have a pivotal role to play in Yemen’s rebuilding once a formal cessation of hostilities agreement is reached. Supporting education reconstruction initiatives that end the militarization of schools and rebuild them with attention to gender dynamics is one critical way for these actors to be involved. These efforts can help shape a future for Yemenis that makes a definitive break from the country’s violent past and moves toward greater reconciliation in society. Such a future would not only secure the human rights of Yemenis, but also aid regional and global stability.

Alexander Kochenburger is the Analysis Supervisor with the Analytical Development and Training team at the New Lines Institute. Before joining New Lines, Alex worked as a senior program assistant at AMIDEAST, studied Arabic with the Center for Arabic Study Abroad program, and completed a Fulbright grant in Agadir, Morocco. He also interned with Search for Common Ground’s program development team for the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia. His research focuses on the role of education reform in transitional justice and conflict transformation efforts.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not an official policy or position of the New Lines Institute.