GCPEA News

Roadmap to 2015: Three-Point Strategy for Education

By Gordon Brown, UN Special Envoy for Global Education

A World at School, September 25, 2014

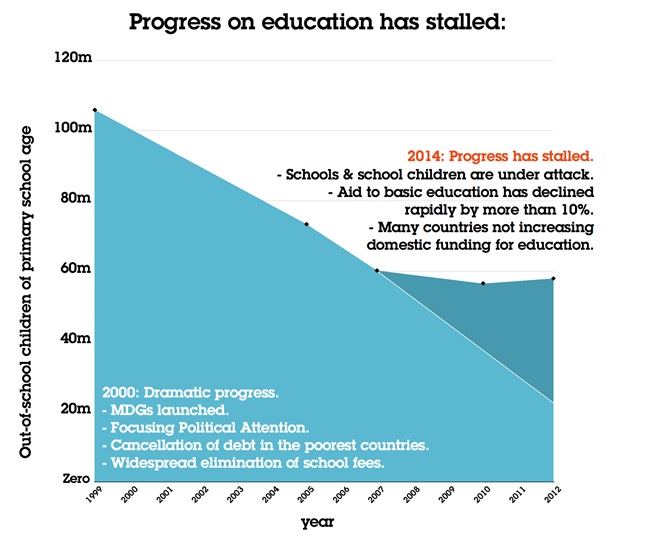

In 2000, world leaders promised that every child would be in school by the end of 2015. As we enter the final stretch, we are still short of achieving Millennium Development Goal 2.

During the first decade of the MDGs, the global community was able to enrol more than 40 million children into school. But in the past several years, progress has stalled.

About 58 million children do not go to primary school and the number of out-of-school children is increasing in some countries. Because funding for access and quality of education is uneven across the world, a further 250 million children are in school but not meeting even the most basic learning levels. And inequities in education financing leave behind the most marginalised, poor and vulnerable.

On the eve of the post-2015 development agenda, the global community’s new set of goals will lack credibility unless we demonstrate that we have done everything possible to keep the promises already made in 2000.

Shifting the priorities in a post-2015 agenda without delivering on our pre-2015 pledges could mean abandoning tens of millions of the most vulnerable children. Our legacy cannot be one of leaving behind those hardest to reach. This failure would undermine the successes we have made and weaken our ability to achieve the even greater targets we have for the future.

Therefore, I propose a three-point strategy for universal education – to ensure quality learning opportunities are provided to as many out-of-school children as possible. Achieving these changes will ensure we live up to the promises made to children and provide the firm foundation needed to finish the job.

Underpinning these three points is the growing leadership of young people around the world who refuse to accept complacency. Young people are mobilising and making their demands heard. And they are being supported by a growing coalition of businesses, faith leaders, NGOS, civil society groups, media and social media, teachers and influential individuals.

Nothing changes without pressure and they are demanding that every child in the world can go to school, without danger or discrimination. They know that education can give them freedom, better health, hope and a future. They are demanding their right to education, no matter who they are or where they were born.

1) Targeted co-ordination

Aid to basic education was cut by almost 10% between 2010 and 2012. Some countries have been subject to massive and rapid shifts in bilateral support. Burkina Faso, for example, lost five donors between 2006 and 2009 – 53% of its total aid to basic education.

An analysis of the 41 countries in greatest need of education support found substantial variations in the amount of aid disbursed. Even countries with the best intentions and the best plans cannot build a sustainable education sector with this level of uncertainty.

In the current scenario:

- Poor countries receive too little bilateral aid and what aid they do receive is uncoordinated

- Multilateral aid is not enough to make up for the lack of bilateral aid

- Financing that is multilaterally coordinated is not always available

- Uncoordinated bilateral aid leads to highly fluctuating, unpredictable financing flows

In 2012, about a third of aid to basic education was supplied by multilateral agencies and about two-thirds was delivered bilaterally. The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) plays an important and leading role in coordinating multilateral education assistance, particularly in some of the poorest countries. However, multilateral donors have not always been able to fill the gaps left by bilateral donors. Of the 41 countries in greatest need, 22 receive less than $10 per child from bilateral donors, even though their need is much greater.

In only 6 of the 22 countries have multilaterals been able to significantly fill this gap. While it costs about $130 to $150 per year to provide a child an acceptable primary education in low-income countries, basic education aid disbursed per primary-age child varies widely from $7 in Democratic Republic of Congo to $63 in Haiti.

To improve financing and delivery, it is essential that we coordinate bilateral aid, plan to fill these gaps between and within countries and build on important coordination lessons learned from GPE. Bilateral coordination is also critical because sometimes middle-income countries faced with high burdens of out-of-school children or specific education challenges – including countries affected by conflict and emergency – are ineligible for international pooled assistance. For instance, despite the influx of hundreds of thousands of refugee children, Lebanon is not eligible for the traditional education financing available to low-income countries.

Improved bilateral coordination could prevent countries that face a sudden crisis from falling through the cracks of the international financing system. In these situations and others, the lack of an international mechanism to coordinate bilateral assistance has a tremendous impact at country level. For instance, Nicaragua lost 5 donors, whose average share of total basic education aid was 35%, from 2006 to 2009. Since 2010, 12 African countries have seen cuts in their aid to basic education of $10 million or more and current aid across the continent is at the same level as in 2008.

Financing availability, strategy shifts and aid cycles must be coordinated at a global level. Though much work is being done by local education groups, bilateral, multilateral and country strategies must be coordinated so that they clearly identify funding gaps as well as the complementary aspects of each agency in supporting education systems and in increasing access for out-of-school populations. Coordination should also increase the ability to respond quickly in times of crisis.

A global coordination mechanism must be established to proactively predict trends of bilateral financing and provide coordination among global donors and multilateral financing agencies.

2) Deadlines for delivery

All governments, UN agencies, development partners, NGOs and civil society organisations must work together to ensure that every country, state and district has a clear action plan.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Pakistan is developing district-level delivery plans aligned with the national education acceleration framework. Lebanon has developed an ambitious strategy for all children – Lebanese, Syrian refugees and vulnerable populations – but still needs the financing. And Nigeria is working to ensure that schools are safe and that individual states work as part of a comprehensive strategy to get up to 10.5 million out-of-school children into school.

Targeting more resources to countries with strategies for out-of-school children could also create sustainable solutions. Existing resources topped up by $6 billion of domestic and international financing targeted at out-of-school populations could provide education for all children.

At country level, planning must focus on the timetable for delivering universal education. While some national plans may already have this explicit target, we must require that every national plan has a deadline and strategy to reach it. Donor strategies can then be mapped more effectively to country-level planning and necessary additional resources can be identified.

3) End discrimination

Millions of children are unable to go to school because of social barriers. They are condemned to child labour, child marriage and child trafficking. Girls also suffer many types of discrimination, such as exclusion and abuse. All of these barriers must be addressed in the context of education. They must be central to the coordination of education financing, the development of timetables and the implementation of national plans.

Around the world, a civil rights struggle is under way, as girls and boys demand their basic right to an education. Civil society pressure and support around the world is critical to eliminating these barriers.

More than 100 organisations – including major UN agencies and initiatives (such as UNESCO, UNICEF and the Global Education First Initiative, as well as the Global Partnership for Education and Education International), and many faith-based organisations, businesses, aid agencies and grassroots groups – are part of the 500-Day #EducationCountdown campaign marshalled by A World at School.

This massive initiative, led by youth and civil society, will advance the agenda and demand results on the barriers that keep children out of school. In each of the campaign themes between now and the end of 2015, partners are identifying measurable, deliverable targets.

For example, 28 million out-of-school children live in conflict areas. The #EducationCountdown targets include securing commitments from 50 countries to protect schools from attack by implementing the Lucens Guidelines.

Other targets include:

- Establishing a revolving fund of at least $100 million to help quickly in humanitarian crises

- Mobilising $177.2 million for more than 400,000 Syrian refugee children in Lebanon

- A $100 million fund for the Safe Schools Initiative in Nigeria

In the fight to end child marriage and stop 14 million girls under the age of 18 becoming brides every year, the #EducationCountdown is initially working to establish the first ever child-marriage-free zone in Pakistan. It is also focusing on eight countries where the legal age of marriage is under 18 and supporting work to change this in accordance with international law. And it is working to ensure that married, pregnant girls or mothers are not prohibited from attending school.

As the #EducationCountdown continues to the end of 2015, civil society will work together to focus on key targets for ending discrimination against girls, abolishing child labour – which keeps 15 million children out of school – and delivering quality learning opportunities for every child. We will need 2.1 million more teachers and improvements to address the needs of the 250 million children who are not learning. The ultimate goal for the #EducationCountdown is to generate equal opportunity for 58 million children and ensure every single child is in school.

Conclusion

We can be the first generation to develop all the talents of all our children. This achievement does not require an amazing scientific breakthrough. We have everything we need to make it happen – except political will. We need that and we need to improve the coordination of bilateral and multilateral financing, develop timetables and target resources and address critical barriers to education. We need to act now and make this moment the most critical turning point for access to education for the most vulnerable children.

What makes me believe this is possible? Not only strong leadership in some of the key agencies but the increasing connectedness of civil rights groups in different countries – led by young people and spurred by communication across the internet and global civil society movements.

We have continued to witness attacks on schools, teachers and children. In response, young people around the world are increasingly speaking out about the boys and girls shelled in their schools in Gaza, schoolgirls abducted in Nigeria, Syrian refugee children without homes and schools, and millions of children denied basic rights including the right to education. Young people clearly see the connections between these tragedies and the forced marriages of nine and 10-year-olds, rape, genital mutilation and other abuses of girls and the denial of girls’ basic rights. An attack on one school child is an attack on all school children.

Young people are demanding not just their own rights. They are demanding that no child, no teacher, no school should be a target in conflict. That all children everywhere should have the opportunity of a quality education. That girls should have equal protections and equal opportunities under the law and in practice.

This week youth activists from more than 100 countries are launching #UpForSchool – a global call to action to demonstrate the demand to get all children in school and learning by 2015 as promised. They are asking us to join them and rise #UpForSchool. As part of this movement, youth will collect signatures across villages, towns and cities in their countries to demonstrate that the commitment exists to fight for education for all children – particularly the most vulnerable and excluded. They will create a groundswell of pressure that no government, no politician, no leader can ignore.

They are being supported by a growing coalition of businesses, faith leaders, NGOs, civil society organisations, teachers, media, social media and influential individuals.

The action needed to get every child in school will not happen until politicians and leaders feel the pressure to make the urgent political and financial commitments necessary to tackle the key barriers to children being in school.

Some of these young people are coming to New York this week to shadow the UN General Assembly and ensure that the rights of children is high on the international agenda. I am inspired that these youth – a fraction of those working every day around world – continue to apply pressure and that their calls are being heard at the highest levels.

Listening to these youth and delivering on our previous commitments – for both governments and the international community – will be the key to success.

Along with global and country roadmaps, everyone – including faith-based organisations, business leaders, youth, civil society, NGOs and teachers – must be encouraged to deliver results.

Young people are taking the lead in pursuing this agenda. It is now the turn of the global community to shake off its complacency.

Nothing changes without pressure. Join them and rise #UpForSchool.