GCPEA News

UK refuses to sign UN document protecting schools in war

The Telegraph, February 7, 2016

By Richard Spencer, Middle East Editor

Philip Hammond, the Foreign Secretary, has been accused of vetoing a request for Britain to sign up to a UN initiative to prevent schools and schoolchildren from becoming victims of war.

Unicef, the United Nations children’s fund, along with children’s charities, is promoting a “safe schools declaration”, setting out guidelines for how armed forces can avoid targeting schools in war.

The initiative, which has been signed by 51 countries already, is being launched in Britain as gruesome pictures emerge from Syria, Yemen and elsewhere of children bombed and maimed in conflicts there.

But Britain has refused to join up, even though it was drafted by a former British naval officer, Steven Haines, now a professor of international law.

Ministry of Defence officials, scarred by accusations of abuses against British soldiers in Afghanistan and Iraq, are said to be afraid of creating another “rod for their own back” by extending human rights laws.

Unicef had hoped that following the success of the campaign led by the former Foreign Secretary William Hague along with the actress Angelina Jolie on preventing sex crimes in war, Britain would be a leading participant.

Its voice is considered crucial in persuading other permanent members of the UN security council to “set standards” in the practice of war. None of the other four members – the United States, France, Russia and China – has signed either.

However, Foreign Office interest in the project is said to have come to an end when Mr Hague was replaced as Foreign Secretary by Mr Hammond, who had previously been Defence Secretary.

Prof Haines said that both the Foreign Office and Department for International Development (DFID) had been keen beforehand. “The stumbling block was Philip Hammond at Defence,” he said.

When Mr Hammond “moved across” in a cabinet reshuffle in 2014, it meant both ministries were against the idea and contacts at the Foreign Office working on the policy stopped doing so, he said.

“It’s very frustrating,” he said. He said the declaration was by no means a tough one for the government to enforce. “There’s no way that I was going to draft something that would embarrass the British government.”

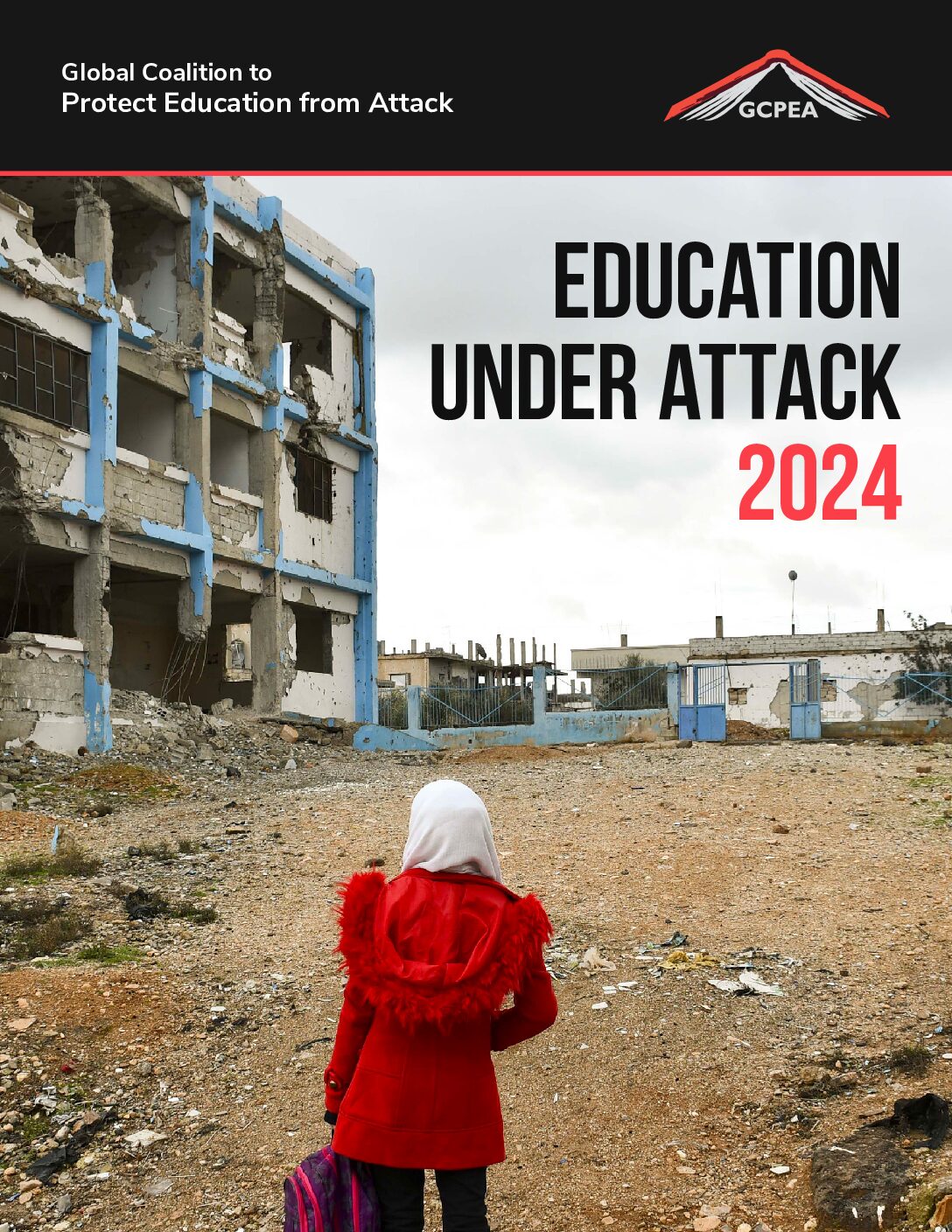

The last few years have seen terrible images emerge from battlefronts, enabled by social media, demonstrating the full effects of war on civilian life.

Many pictures – showing children cut literally in half, or otherwise maimed – are too gruesome to be shown in most newspapers or other professional media, but have circulated widely on Twitter and Facebook.

Schools are often targeted because they make good strongpoints in urban warfare – as military bases, prisons, and storehouses for weapons. A number of UN-funded schools in Gaza were revealed to have been used by Hamas to store rockets, after an outcry over the killing of children in Israeli bombardments in the war of 2014. Schools have been used as bases in both Syria and Yemen.

But that means that other schools still in use come under suspicion, and hit, often from the air.

The declaration commits signatory states to try to enforce six guidelines, the most important of which prevent military forces using functioning schools as military bases where they can become legitimate targets.

They say that while it is accepted that schools that are not being used for teaching are brought into service on occasion, this should be done only where there is “no viable alternative”. If forces on the other side see schools being used in this way, they should consider “all feasible alternatives” before attacking them.

The declaration was launched in Norway last year, in the presence of, amongst others, the father of Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani girl shot and injured by the Taliban. It is strongly backed by the former prime minister, Gordon Brown.

Leah Kreitzman, a spokeswoman for Unicef, said there was no suggestion that British forces were likely to break international law in this area itself. But she said that both governments and “non-state actors” had been guilty in recent conflicts.

Britain could have an impact on international practice, particularly as it plays a major role in training other militaries.

“Fifty governments have signed up and we are encouraging the UK to do the same,” she said. “We want it to show leadership.”

The Ministry of Defence is believed to fear that the declaration goes beyond existing humanitarian law, and that though its “guidelines” would not be enforceably legally, they could still be used to embarrass the military. It is already facing a long-running series of accusations of abuses by soldiers fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Britain is also facing allegations that it is directly or indirectly responsible for alleged war crimes committed by its close ally Saudi Arabia, using British-supplied weapons, in its war in Yemen.

Officials believe that current humanitarian law is sufficient, and oppose further constraints.

A Foreign Office spokesman said: “While we support the spirit of the initiative, we have concerns that the Guidelines do not mirror the exact language and content of International Humanitarian Law and therefore the UK, along with several other countries, was not able to sign the Safe Schools Declaration in Oslo in May 2015.”