GCPEA News

‘Where we used to go to teach … the armed men take us to torture us’

The Conversation, July 29, 2013

Kate Robertson, Deputy Director, CARA,

The Council for Assisting Refugee Academics (CARA) helps academics at risk of persecution, discrimination or violence so that they can carry on their work.

CARA was established in 1933 by leading British academics and scientists of the day to provide refuge and support for academic colleagues who were being forced by Nazi discrimination and violence to leave Germany and Austria. Sadly, the need to protect science and learning did not end with Hitler’s defeat and our work is as important today as ever.

As CARA deputy executive Director, my job is to facilitate periods of sanctuary to academics in conflict- and crisis-affected countries, to allow them continue their work in safety, in partnership with UK academics and universities. This is a statement from a Syrian doctor and academic attached to Damascus University, who has turned to CARA for help.

I’m writing from Syria, but it’s not the Syria I knew and loved. People today have lost the sparkle in their eyes because they’ve lost their faith in life. Men, women and children are walking around with pale faces, lacklustre smiles and no joie de vivre. People everywhere look stunned as if their minds and souls are far away.

We’re stranded here in Syria with our fears, losses and disappointments. Together we face an uncertain future. Everywhere you go people are suffering and mourning, especially the young academics and students who have lost all hope of a better life. Their motivation has been replaced by a total sense of helplessness and despair.

I am one of those who have lost their youthfulness as a result of the crisis. Despite being 26 years old, my life-long dream of a hopeful academic future is being destroyed before my very eyes. I believed I was born in Syria, the most peaceful place in the world. It was so.

I remember how we were living in peace and love. I remember how we listened to bird song. I remember how we smelled the fragrant flowers and roses.

Today, the only sounds our ears recognise are the sound of bullets and the thunder of rockets. Today, the only smell that our noses recognise is the smell of gunpowder and piles of corpses.

You can’t even imagine what we’ve seen – what Syria has seen. We never thought that our beautiful country would become what it has today. Whatever the words that may be used to describe the situation, no words would ever rightly describe the crisis. I can say that, as one who lives in the crisis.

Lost generation of academics

As the crisis in Syria enters its third tragic year, and the daily headlines focus on military clashes and political efforts to resolve the crisis, the world must not forget the human realities at stake. Education is a basic human right. The risk of losing a generation of students grows with every day the situation deteriorates, while the progress of previous years is undone.

All around us, our dreams and opportunities for the future are being lost, our dreams and rights denied. We face tremendous dangers on a daily basis. We are being killed and maimed by conflict. We are dying because we want to learn. I am writing from Syria, the country where the literacy rate among youth, just two years ago, according to UNESCO, was approaching 90%.

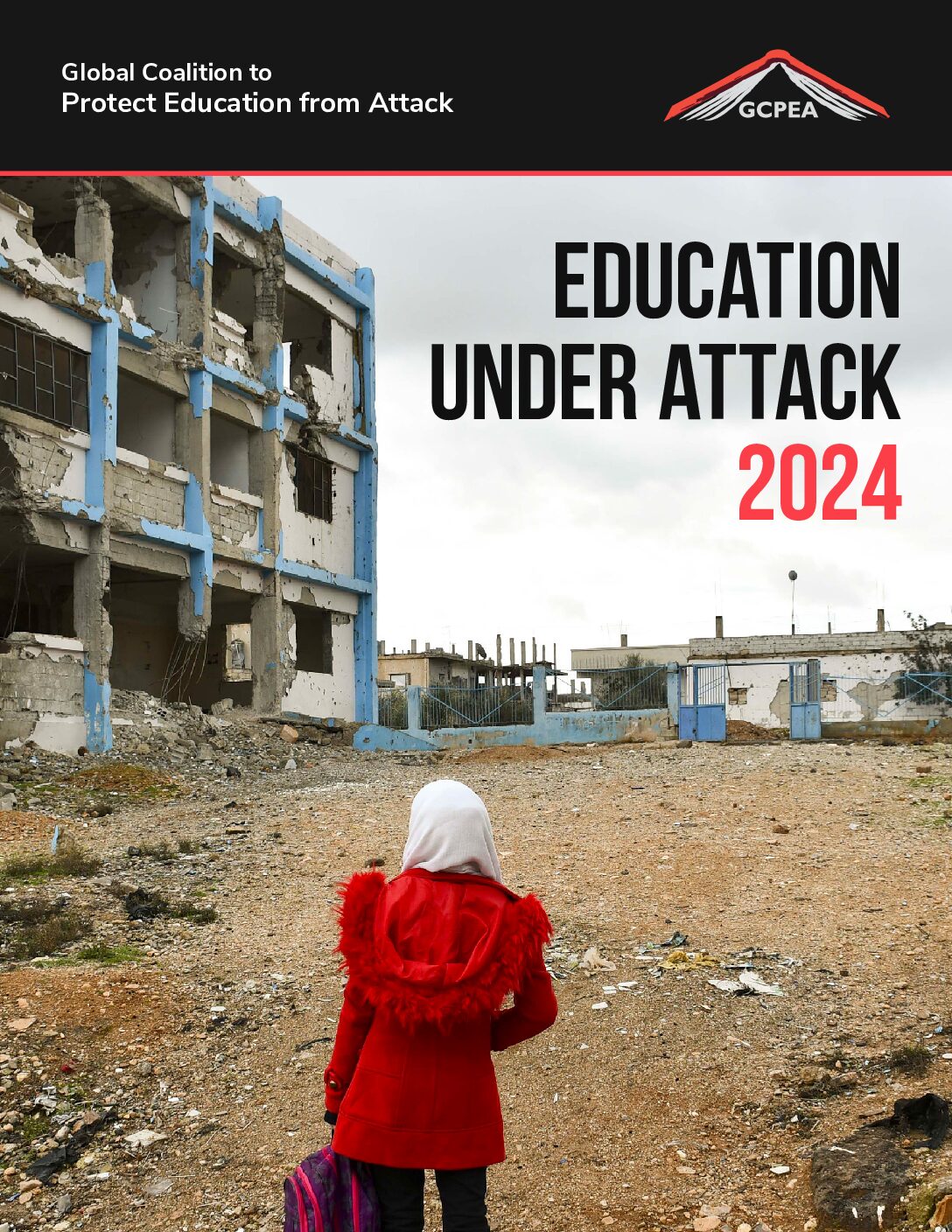

Today, I do not know what the rate is, but I know exactly how massive the destruction of our educational infrastructures has been. Thousands of our schools and educational institutions have been completely destroyed.

Schools now shelters

Educational institutions that are not destroyed have become jails and torture centres occupied by the armed groups. The same places we used to go to teach or to learn, the armed men take us there to torture us. There was nothing they would not use to hurt us. Hundreds of what were previously known as “schools” have become shelters for displaced people, and horribly overcrowded.

Worldwide, education is a basic human right. Today in my country we have to access this right in a different way. As academics and students, when we leave our houses going to schools and universities, before each departure we have to say warm farewells to our families for fear that we may never come back, or see each other again.

For hundreds of our academics and students who left their homes in this way, it has been their final departure. What came back to their homes was their remaining organs and their carnage.

At the centre of the capital, on March 28, 2013, mortar shells attacked the campus of Damascus University where I work and study. The shells killed dozens of our students, and wounded dozens of others. The same tragedy happened at University of Aleppo, where some rockets hit the campus. At least two bombings left more than 80 people – mostly students – dead. I don’t know whether they had said goodbye to their family before they left their homes, but I know they left us forever.

I don’t know whether we should get used to this as “routine”, but the “routine” that I know we should get used to is the car bomb explosions, anywhere and anytime. We depend on our luck to survive, but may not have the same survival chances when faced with kidnapping, assassination, sniper shooting or even torture.

Dying for knowledge

Many of our scientists and scholars have been killed and many others were liquidated in different ways. Maybe it is the cost of knowledge. As a postgraduate student, that may be my fate, however, as a doctor, my fate may be more bitter.

Since I was a child, my lifelong dream was to become a world-ranked doctor who always does his best to improve the quality of life of his patients. My lifelong dream was my stimulus to be always a top student in my class. However today, my lifelong dream is the stimulus to kill me.

Here, in what was the most peaceful place in the world, my guilt is that “I am a doctor”. It has become the “right” of the armed groups to kill us, because we are doctors. This is our luck. This is what we should learn on daily basis. Moreover, if a doctor is being killed by a gunshot, believe me, it’s good luck. Many others have been tortured to death and yet others maimed.

I don’t know what your feelings would be when you realise that one of your colleagues has been killed in this way. I don’t know what your feelings would be when you hear this on a daily basis. As a Syrian doctor, my luck is to live where the law of the jungle is becoming the dominant law.

At the time of writing this message to the world, I have survived several murder attempts when going to work my nightshift at Damascus University Hospital. I think “luck” is playing a role at the moment. I am not sure whether luck is still at my side. Sometimes, I think I survive because of my noble duties serving patients.

I am not sure I became a military target because of “myself”, but I am sure I became a military target because of my sacred duties as a doctor. I believe they want to destroy our community infrastructures; the medical, the academic and the educational ones. I am saying this because I am not the only one. Many of my colleagues have received threatening letters to stop going to hospitals. Whatever the cost, our priority is always to serve the patients, even at the expense of our survival.

When will my turn come?

Every morning, when I go to my work I ask myself the same question. I go to the hospital every day as a doctor who does his best to save the life of victims of Syria crisis. Should I await the day when I go there as a lifeless body – a victim of the same conflict?

Yes, I would like to leave my country, but not because of I am afraid or fearful, at all. My aspiration is to get further medical expertise in order to contribute more effectively to medical services in my own country, where my patients eagerly await me. My country is in need. No one is helping and we are dying.

Now, I feel that no one cares about Syria. All organisations I have contacted have apologised in one way or another. Others when they realised the tragedy in which we live, they did not send any reply. Maybe they felt ashamed to send me a negative response.

I have never felt so helpless and hopeless as when I imagine my educational future being destroyed before my very eyes. For me, education is the essence of my life, even more than air, water and food.

Because I am still alive, I can ask for help. Today, I knock on the door of CARA, my last hope. To whom it may concern, to anyone, hear my words.