GCPEA News

Ensuring the Continuity of Conflict-Sensitive Education during War: Lessons from “Education under Attack 2024”

World Peace Foundation, August 21, 2024

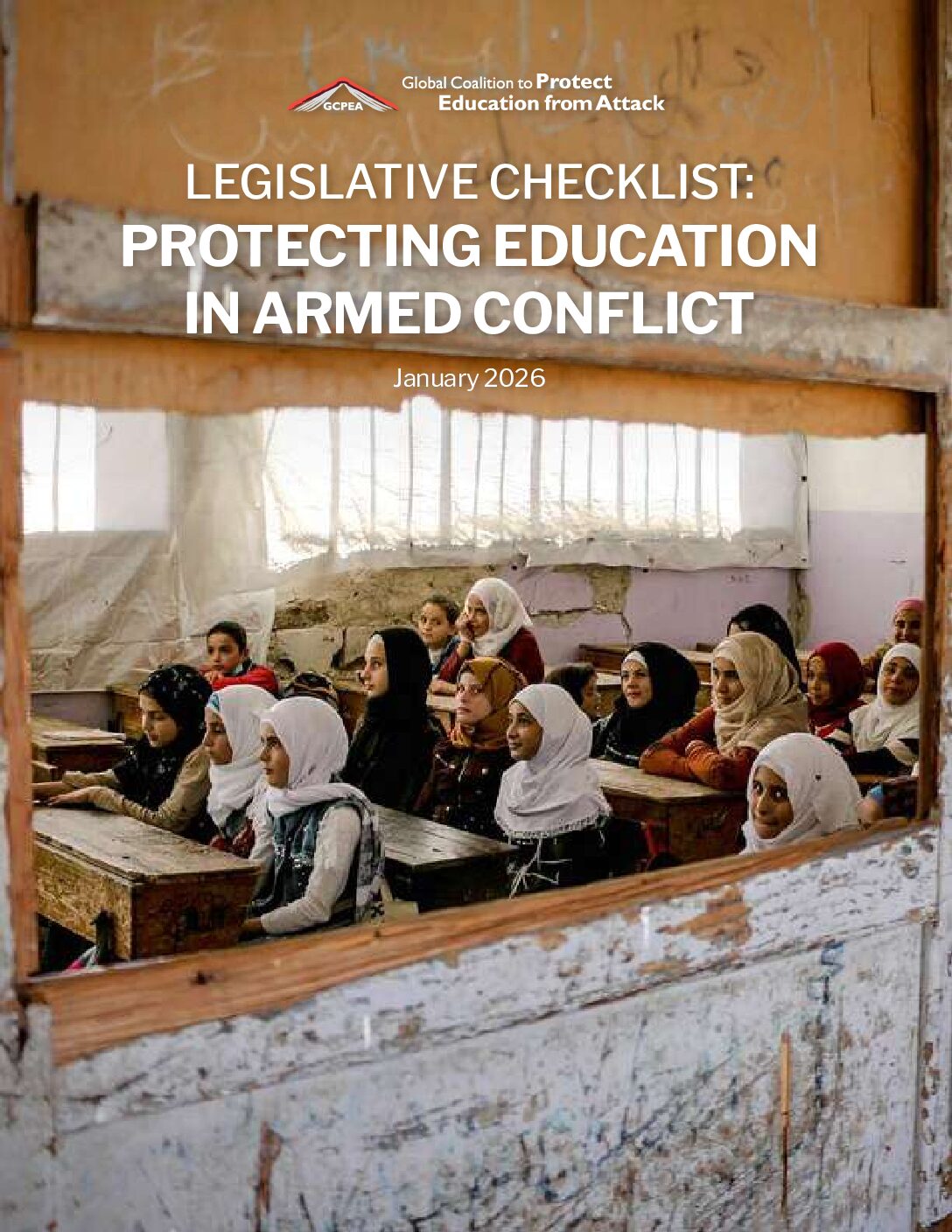

The number of grave violations against children in conflict zones hit a record high in 2023, and a disturbing number of these breaches took place in and around schools. In 2022-2023, the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (GCPEA) identified more than 6,000 attacks on education in armed conflict – a 20% increase from the previous two years. These trends are deeply alarming, and they demonstrate the urgent need for the international community to revisit efforts to better protect children and education in armed conflict. This work will inevitably require investments in a number of areas, including greater accountability for perpetrators of attacks on education and non-discriminatory assistance to victims. However, protecting education in armed conflict also means ensuring that children do not lose access to schooling, and that wider education systems are conflict-sensitive. Doing so not only helps protect children in the short term, but lays the foundation needed for post-conflict reconstruction and more resilient societies over the long term.

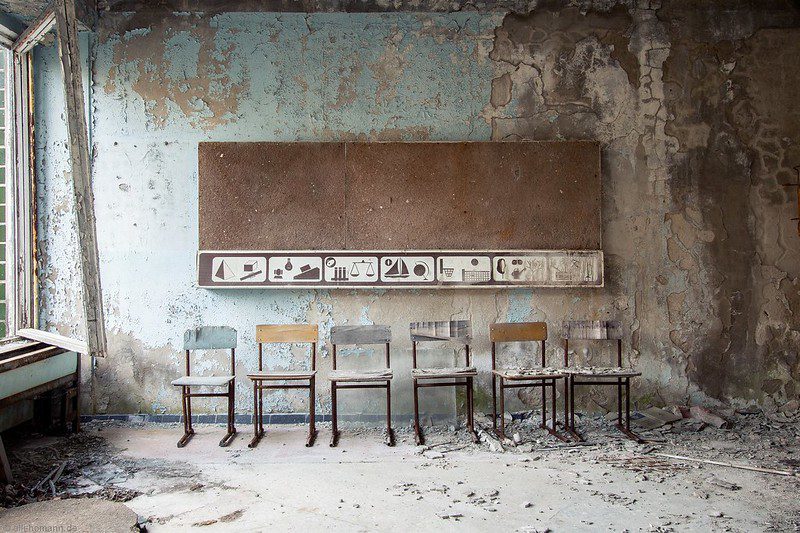

GCPEA’s latest report, Education under Attack 2024, found that 28 countries suffered from a systemic pattern of attacks on education in armed conflict in 2022-2023. Attacks included the shelling of schools by Israeli forces in Gaza; the looting, burning, and vandalization of education facilities by armed groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; the military occupation of schools by Russian forces in Ukraine; and the violent repression of demonstrations by university students in Sudan. The significance of these devastating attacks lies not only in the ensuing physical and psychological harm and loss of life to students and educators, but also in the damage to the very educational infrastructure needed for post-conflict reconstruction and reconciliation.

Over the long-term, attacks on education can prevent students from returning to school for extended periods of time, depriving them of access to critical resources such as feeding programs and health services, opportunities for self-advancement, and skills needed to contribute to the workforce. Given that attacks on education disproportionately affect young women and girls and students with disabilities – groups that face greater obstacles in accessing and resuming their education – attacks can also entrench and exacerbate existing societal inequalities. Attacks on education may additionally spur the exodus and censorship of academic communities, hindering research and development. All in all, attacks on education take many forms, but they inescapably impede political plurality, accountable government, and prosperous societies.

Recognizing the urgency of protecting education in armed conflict, over 120 countries to date have endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration (SSD). An international political commitment to protect education during war, the SSD was drafted in 2015 through a process of consultations with UN Member States led by Argentina and Norway. The agreement stipulates that endorsing states will maintain access to education during armed conflict, develop conflict-sensitive education systems that promote peace and respect, ensure that victims of attacks have access to the justice system to pursue accountability, and other related assurances.

While the continued rise in attacks on education in armed conflict is deeply troubling, we have already witnessed the ways the SSD can help. Over the course of 2022-2023, GCPEA identified numerous positive developments in protecting education from attack, including in the spheres of implementing conflict-sensitive approaches to education and ensuring educational continuity even during armed conflict. These initiatives were realized in many different parts of the world, and were driven by contributions at the communal, national, and international levels.

In Mopti, Mali, community members utilized the SSD to negotiate the re-opening of schools through direct engagement with an armed group. These efforts were aided by international organizations who translated the SSD into Bambara, Fulfulde, Sonrhai, and Tamasheq and conducted awareness raising activities within the community. Elsewhere in the country, communities in central Mali engaged armed groups in discussions to re-open public schools. The successes of these measures are not necessarily applicable across contexts, but they do underscore the ways in which international initiatives like the SSD can be leveraged by affected communities to successfully address local objectives. Previously, the Ministry of Education in Mali took an important step toward ensuring conflict-sensitive education by including protection against gender-based violence as a topic in the national curriculum.

In Ukraine, the Ministry of Education and Science has been working in partnership with multilateral organizations to support the continuation of education for the more than 5 million children facing barriers to access during war. These efforts range from rehabilitating bomb shelters in schools, issuing laptops and other learning materials to displaced students and educators, and expanding online learning systems. Multilateral organizations have also supported the development of tools for teachers to provide mental health support to students, as well as advice on how to stay safe amidst the fighting.

Many more positive developments like the actions taken in Mali and Ukraine over the last few years are needed to ensure that schools are safe havens and never battlegrounds. In Gaza, where students are eager to resume learning, the catastrophic density and intensity of violence has made the scaling up of critical education in emergencies infrastructure near impossible.

When education continues in conflict-affected contexts, it provides a critical sense of normalcy, safety, and routine for students struggling to continue their lives despite the violence raging around them. It also positions them to help their country rebuild once the conflict subsides. When education is conflict-sensitive, it takes into account the unique needs of students and educators during wartime and addresses the ways in which education itself can drive or assuage conflict in areas related to language of instruction, ease of access, staff recruitment and deployment, and curriculum content. As attacks on civilians, beyond just attacks on education, rose more than 72% from 2022 to 2023, it is imperative that the international community reinforce protection efforts and embrace the ways in which resilient and conflict-sensitive education systems can facilitate post-conflict reconstruction and long-term peace.

————————————–

Author

Alexander Kochenburger is a Coordinator at the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack. He supports GCPEA’s programmatic work, including through assisting the Coalition’s advocacy and research efforts as well as managing its communications and finances. Previously Alex worked at the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy as an analysis supervisor and at AMIDEAST as a senior program assistant. He also completed a Fulbright grant in Agadir, Morocco from 2017-2018. Alex obtained a Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy from The Fletcher School at Tufts University and a Bachelor of Arts in International Studies and Arabic from the College of the Holy Cross. He has an advanced proficiency in Arabic.