GCPEA News

Sheikha Moza: The power behind Qatar’s global lessons

BBC News, November 12, 2014

By Sean Coughlan, BBC News education correspondent

The goal of universal primary education, a promise broken for decades, can be achieved in the next seven years, says Sheikha Moza bint Nasser.

The senior member of the Qatari royal family and education campaigner wants to galvanise the international community to provide education for 58 million children around the world without access to school.

World leaders made a millennium pledge this would be reached by 2015 – but this deadline is almost certain to be missed.

The target is likely to slip back to 2030. But Sheikha Moza, married to the former ruler, and mother of the current ruler of the wealthy Gulf state, says it could be reached in half that time.

It might be a case of royals not wanting to be kept waiting, but she calls for a much greater sense of urgency.

“It can be achieved. But we really need people to commit themselves. We need politicians to understand the power of education for their own countries, for their economies. It should not be seen as a luxury. It is essential.”

Soft power?

But how is this going to happen?

Sheikha Moza has a seat on high-powered UN education committees, but she can also harness the formidable financial resources of oil and gas-rich Qatar.

She has launched her own campaign, Education Above All, which aims to get an extra 10 million children into school at a cost of about $1bn (£630m) with about a third of this coming from Qatar.

But why is education such a passion? Not just for Sheikha Moza, but for Qatar? The Gulf state funds a huge range of projects in more than 30 countries, often in places with no apparent strategic interest. Half of the country’s overseas aid budget goes on education, which must surely be the highest proportion in the world.

The conventional wisdom is that Qatar’s educational largesse is a form of soft power, exerting influence through culture and learning.

But Sheikha Moza, speaking in Doha at the annual Wise education summit, rejects this.

“I never thought about it like that. People always think that you should link your foreign aid with your national interests. Does it need to be always like this? I don’t see it this way. I see it as a global responsibility towards others.”

After the oil

The country’s initial push for education was entirely practical, she says. Qatar needed to plan for a time when the oil and gas runs out – and that meant building an education system to support a different type of modern, knowledge-based economy.

“My intention was to build a strong, solid infrastructure for research and development. To do that, Qatar needed a stronger education system.”

Sheikha Moza is chairwoman of the Qatar Foundation which took on the epic task of creating a higher education system from scratch. There are now nine universities on a huge Education City campus, built in partnership with US, French and UK institutions.

It might have become a meeting point for west and east, with Qatar a country at the global crossroads, but it wasn’t intended that way, she says. It was about building up education as an insurance policy for when the money runs out.

“It wasn’t planned to be like this, to be frank with you. We didn’t design our education to be a bridge between different cultures… We were thinking inward.”

But there is now an outward ambition. Often in the unlikeliest of places.

Many children without schools are caught up in conflict and she is campaigning for refugees, who might spend many years in “temporary” camps, to have better access to education.

‘Angry and frustrated’

She has visited camps in Turkey and Kenya, saying that families might have “lost their dignity, their pride, their possessions, their homes”, but they should not lose their chance of an education.

“It makes me angry and frustrated because we can do something about it. I think this is a result of our negligence. I think people are preoccupied with other things they feel are more important. But these are human beings, they deserve some quality of living.”

She is now working with the UNHCR on integrating education into refugee camps.

“Until now, the priorities have been shelter first and food second and the rest can come later. I think these kids need education. I sat with the parents, they know the importance of education for their kids.

“But they are faced with daily obstacles. Some cannot send their girls to school because there was no electricity. Children have to walk miles to reach the schools. During their journey they might be kidnapped or attacked. It’s a horrible situation.”

The highlighting of attacks on education is another below-the-radar offshoot of Qatari funding.

The abductions of schoolgirls in Nigeria – and the suicide attack this week on a school – have drawn attention to the deliberate targeting of education.

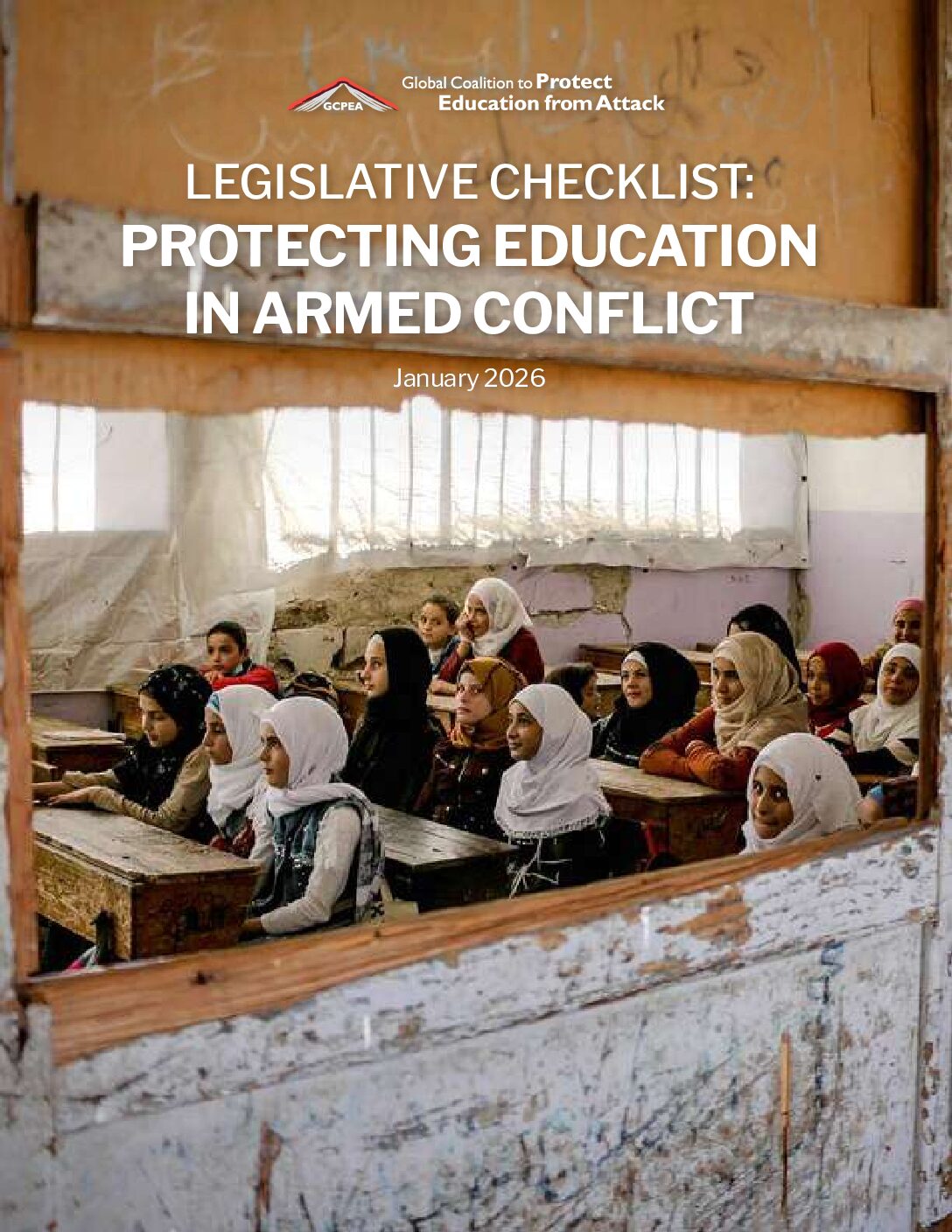

But the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack has been painstakingly tracking this grim phenomenon, recording 10,000 acts of violence against teachers and pupils.

Girls’ education

Sheikha Moza doesn’t accept that such attacks are about a “clash of cultures” or an ideological “clash of civilisations”, but a side-effect of conflict and war. The challenge, she argues, is to stop it and Qatar has promoted the idea at the United Nations of criminalising acts of violence against education.

“We succeeded in achieving this. But the thing is that there is no enforcement of such resolutions. So people still attack schools.”

If Boko Haram is trying to disrupt education for girls, the Wise Prize, awarded by this conservative Islamic country, has supported a charity fighting for equal access for girls in education.

The winner, Ann Cotton, founded Camfed, which works in five African countries to help more girls stay in secondary and higher education.

In terms of discrimination against girls, Sheikha Moza says: “Of course, girls need to be educated in the same way that boys need to be educated.”

There is no escaping the contradictions in Qatar. It is a deeply traditional country, with a strong Islamic identity. But it’s also a place of restless change, filled with modern technology, importing ideas and cultures, with a skyline in a constant state of re-invention.

It occupies a peninsula jutting out into the Persian Gulf, like a small hand holding something expensive, with Saudi Arabia on one side and Iran just across the water. The Qataris have faced accusations over the funding of extremists in Syria, but they also play host to a major US airbase.

Balancing act

Can education be a way of tackling intolerance?

Education can “open minds” and overcome ignorance, she says. But there’s a tougher message too.

“The word ‘peace’ has been overused to the extent where it can carry no meaning. I think that education can help people reach the notion of co-existence. We don’t need to love each other, but we need to understand that we live with each other. We have to co-exist.”

She says that Qatar’s education drive has to find a balance between embracing globalisation and protecting their own local identity.

“Sometimes globalisation can delete one’s identity. But we try to preserve both.”

So what do you give to the woman who has everything? In this case, it seems the answer is a better education system.